Tet traditions

The Lunar New Year, also known as Tet Nguyen Dan, is the most significant and sacred festival of the year for the Vietnamese people. It is also referred to as “tết cả”, “tết ta” or “Lunar New Year” to distinguish it from the Western Gregorian New Year. Tet Nguyen Dan marks the beginning of a new year, symbolizing the transition between the old and the new year. It is a time to conclude the events of the past year and look forward to good things in the new year. Tet celebrations start on the 23rd day of the twelfth lunar month of the old year and end on the 7th day of the first lunar month of the new year, with many solemn ceremonies taking place both in the royal courts and among the common people. All work is temporarily halted for ancestor worship, rest, family reunions, visits to relatives, and the exchange of good wishes…

In traditional folklore, the customs of Tet Nguyen Dan are diverse and richly imbued with national cultural identity. These include worshiping family ancestors and deities, hanging Tet paintings and couplets, setting off fireworks, making Chung cakes, asking for the first writing of the year, giving Tet greetings, celebrating age, and enjoying the Tet flower tradition.

To prepare for Tet Nguyen Dan, about ten days before Tet, families usually repair and decorate their houses and altars… Both adults and children are busy completing the last tasks before stepping into the new year, hoping for a prosperous and abundant Tet.

Tet food preparation traditions: The culinary traditions of Tet, represent a convergence of the quintessence of nature with a wide array of distinctive and diverse dishes. A traditional Tet feast is incomplete without Chung cake (banh chung), Day cake (banh day), red sticky rice (xoi gac), chicken, spring rolls (nem), pork sausage (gio lua), fried sausage (gio xao), jellied meat (thit dong), pickled onions (dua hanh), bamboo shoot soup with pork skin (canh mang bong bi)… During the three days of Tet, every family member enjoys various types of candied fruits made from ginger, coconut, kumquat, lotus seeds, along with roasted watermelon seeds, pumpkin seeds, peanut candy, and pork terrine candy. Traditionally, Tet was also an occasion for people across the country to present regional specialties to the king, which included Phuc linh cakes, lotus wine, and chrysanthemum wine (ruou cuc).

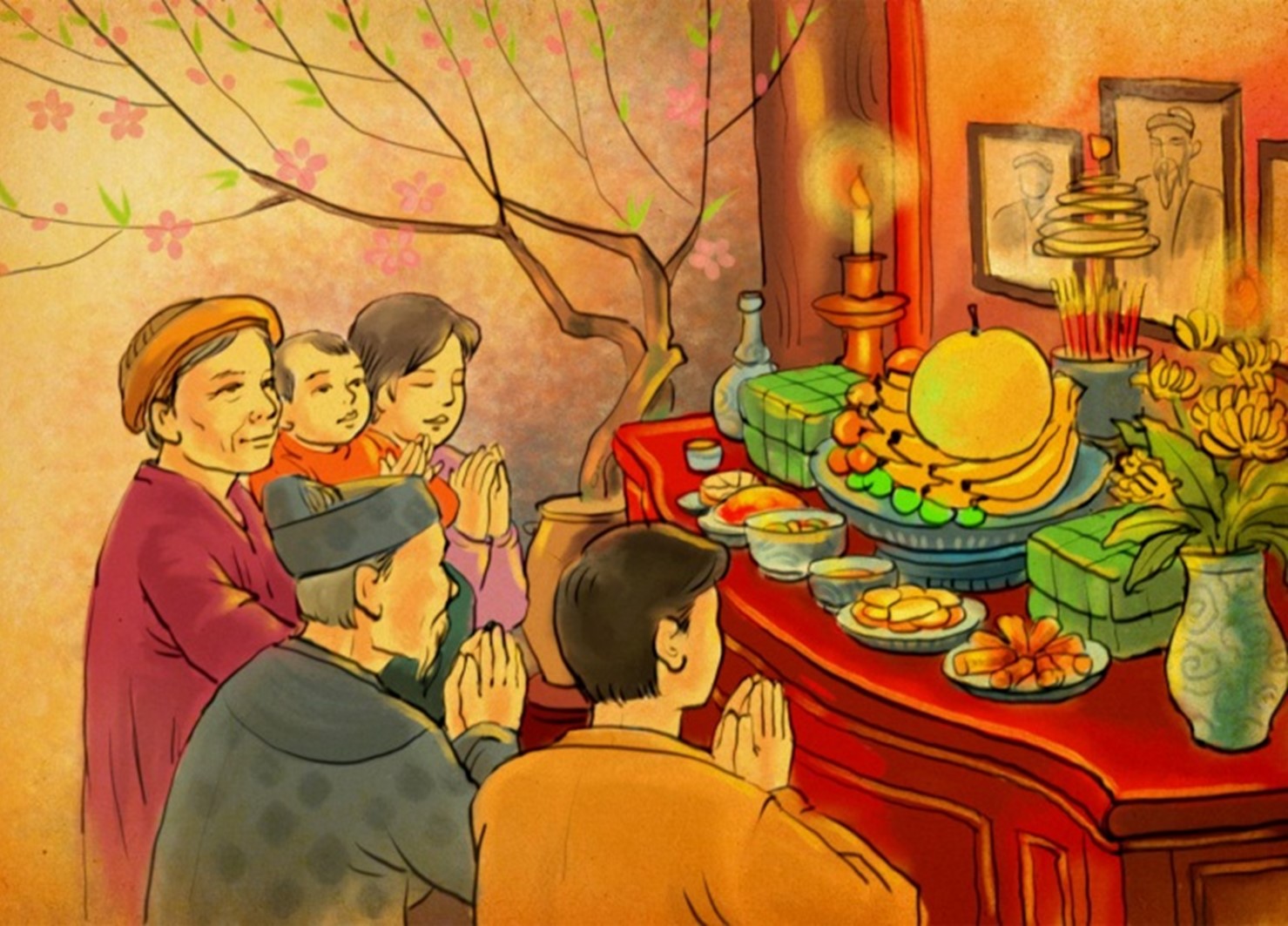

Ancestor and Deity worship traditions: are an indispensable tradition during Tet, reflecting the beauty of Vietnamese culture.

On the 23rd day of the last lunar month, after the ceremony of cleaning the altars, families conduct a worship ceremony for the Kitchen Gods (Tao Quan) who are believed to ascend to heaven. Families prepare the five-fruit tray, various Tet sweets, and candies to offer on the ancestral altar. On the evening of the 30th day, the year-end worship ceremony (Le cung tat nien) is held to inform ancestors that the old year has ended. The night of the 30th is reserved for the Le Tru Tich ceremony, to see off the old year’s guardian deity and welcome the new year’s deity. The morning of the first day of Tet is for the Nguyen Dan worship, meaning the early morning worship of the first day of the year. On the afternoon of the first day and the entire second day, families prepare for the morning (Le chieu dien) and evening (Le tich dien) worship ceremonies. On the third day, families often perform the Le cung ta hoa vang ceremony, a ritual to offer thanks and burn votive paper.

The five-fruit tray (Mam ngu qua) is an array of five different fruits symbolizing the five elements according to Confucianism: Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth. These elements are believed to constitute the universe. The tray’s profound meaning represents filial piety and the hope for a full, prosperous, and peaceful life. In Northern Vietnam, the five-fruit tray typically includes bananas, watermelons (green), pomelos, Buddha’s hand fruit, oranges, tangerines or kumquats (yellow), persimmons, chilies or apples (red), peaches or pears (white), plums or grapes (black)…, where the bunch of bananas is placed at the bottom, a pomelo in the middle, and other fruits arranged around it.

Year-end worship ceremony: On the evening of the 30th day of the last lunar month, Vietnamese families meticulously prepare a rich and savory feast, arranged solemnly with incense, flowers, votive papers, Chung cakes, and other items for the year-end worship ceremony (Cúng tất niên). From the dinner on the eve of the Lunar New Year, before the transition to the new year, families light incense to invite the spirits of ancestors and deceased relatives to join them for the meal and celebrate Tet. In every Vietnamese household, the ancestral altar holds a significant place. The altar during Tet embodies the Vietnamese people’s remembrance and respect for their ancestors; it is carefully adorned with a well-selected five-fruit tray and a feast featuring delicious dishes or favorite foods of the deceased.

New Year’s Eve ceremony (le tru tich): The New Year’s Eve ceremony, held at midnight on the 30th day of Tet, also known as the Tru tich ceremony, is considered the most important ritual, symbolizing the farewell to the old year’s reigning deity (Hanh Khien) and the welcoming of the new year’s deity. Starting at 11 PM on the 30th day of Tet (transitioning into the hour of the Rat in the new year), an offering tray including boiled chicken, sticky rice, Chung cake, betel and alcohol, incense, and votive papers is set up outdoors to worship the governing deities and the celestial soldiers and generals. After the New Year’s Eve worship, offerings are made to the Earth God (Than Tho Cong), the deity overseeing the land and soil of the family. Completing all these rituals marks the true arrival of Tet for the family.

First-morning meal offering: On the morning of the first day of Tet, many Vietnamese families tend to wake up late due to staying up the night before to celebrate the arrival of the New Year. Upon waking, it is customary to prepare a meal offering to the deities and ancestors for the first day of the new year. This practice stems from the belief that during the three days of Tet, the souls of ancestors reside on the family altar, joining their descendants in celebrating the festival. Therefore, it is common to prepare meal offerings each morning from the first day of Tet until the day of the “burning of votive paper” ceremony. Some families are even more meticulous, preparing meal offerings twice a day, in the morning and the evening, with the hope that the souls of their ancestors are well provided for and lack nothing.

The burning of votive paper ceremony: traditionally held on the third day of Tet, involves burning votive paper offerings that were placed on the ancestral altar during the Tet festival. This ritual symbolizes sending off the spirits of the ancestors back to heaven after they have joined their descendants for the Tet celebrations.

Tet couplet hanging tradition:

In traditional Vietnamese culture, the practice of hanging Tet couplets is not only a refined pleasure but also a display of intellectual wit and the art of wordplay. These couplets are considered a quintessential aspect of cultural heritage, serving as a spiritual delicacy during Tet.

Tet painting hanging tradition:

Initially, ancient Vietnamese hung paintings to ward off evil spirits. Over time, this practice evolved mainly into a means of decorating homes to “bid farewell to the old and welcome the new,” with the hope of inviting good fortune in the new year. Typically, after the worship of the Kitchen Gods, families replace old paintings with new ones. In the ancestral worship area, paintings of the five-fruit tray and scrolls are hung high, with couplets on either side, creating a dignified atmosphere. At the entrance, paintings of the “Gods of Wealth and Prosperity” are placed to invite fortune into the home. In the living room, paintings like “Flock of Chickens” or “Herd of Pigs” symbolize the aspiration for abundance throughout the year. The paintings of “Vinh Hoa – Phu Quy,” depicting a boy holding a rooster and a girl holding a duck, convey wishes for a peaceful and prosperous new year, with the family having both “boys and girls”… Particularly during Tet, paintings of buffaloes or chickens are hung, symbolizing the spiritual expulsion of the cold, yin energy of winter and welcoming the warm, yang energy of spring… The regions around Thang Long (Hanoi) are famous for three painting styles: Dong Ho, Kim Hoang, and Hang Trong.

Firecracker burning tradition:

According to ancient traditional customs, following the New Year’s Eve worship ceremony, the practice of burning paper firecrackers takes place. Folklore suggests that evil spirits are greatly afraid of loud noises, so the bursting sounds of firecrackers during the New Year are believed to drive away evil spirits and the misfortunes of the old year. Additionally, these sounds are seen as signals welcoming the arrival of the new year. The louder and longer the firecrackers burn, with the firecracker remnants completely burnt, the more auspicious it is considered for the new year.

Tradition of displaying flowers and ornamental trees

The enjoyment of flowers and ornamental trees has become a beautiful cultural aspect of the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, though it’s unclear when this tradition began. This elegant hobby is not just about appreciating nature’s fragrances and colors; it also serves to express worldviews and convey wishes for the upcoming year.

Flowers and plants are placed in various places within the home. On the altar, common choices include chrysanthemums, marigolds, lilies, and fortune trees. The living room is often adorned with peach blossoms, apricot flowers, orchids, daffodils, dianthus, violets, gerberas, and kumquat trees. Each type of flower and plant has its unique characteristics, but all share common meanings symbolizing luck, prosperity, peace, and happiness.

Tet greeting and lucky money tradition:

Vietnamese have a custom of visiting relatives, friends, and teachers to offer New Year’s greetings during Tet. The proverb “First day for father, second day for mother, third day for teacher” encapsulates the tradition of New Year greetings.

On the morning of the first day of Tet, also known as Chinh Dan, family members gather at the home of the eldest relative to worship the ancestors and offer New Year’s greetings to grandparents and elder family members. As per Vietnamese tradition, everyone is considered a year older with the arrival of the new year, hence the first day of Tet is when younger members “wish longevity” to their elders.

During Tet greetings, it is customary for adults to give lucky money to children in red envelopes (Lì Xì). This tradition, which has a long history, stems from the belief that the brightness and the sound of new coins will ward off evil spirits and protect children, ensuring they grow up healthy. The practice of giving lucky money at the beginning of the year is a beautiful cultural custom in Vietnam and many other countries in the region. It symbolizes the best wishes for the new year and is seen as a way to attract good fortune from the early days of the new year.

Requesting and giving calligraphy during Tet:

For the Vietnamese, from ancient times, the written word has been highly appreciated. With the belief that “being literate” is akin to touching the future’s door, the Vietnamese have a tradition of requesting and giving calligraphy during Tet.

There are two types of requests: one for a character and the other for its meaning. People often visit individuals well-versed in literature, especially learned scholars, to understand the meaning before having the character artistically written by a skilled calligrapher. Those preparing to request calligraphy typically bring a modest offering (such as betel and areca nuts, tea, or tobacco) to the home of a respected scholar, a government-awarded literary degree holder, or a locally revered literati.

Individuals sought for calligraphy are often scholars, teachers, or calligraphers known for their virtue, wisdom, and beautiful handwriting. Those requesting calligraphy do so with the hope of receiving blessings from the giver and a character that resonates with their family’s or personal aspirations.

Besides calligraphy of large characters, these scholars also write words celebrating the new spring, often including characters like “Xuan” (Spring), “Tho” (Longevity), “Khang” (Health), “Ninh” (Peace), “Phuc” (Happiness), “Duc” (Virtue), “Phu” (Wealth), “Quy” (Nobility), “Loc” (Prosperity)… Middle-aged individuals often request characters like “Tam” (Heart), “Duc” (Virtue), and “Nhan” (Patience); young men and women might ask for “Danh” (Fame), “Duyen” (Charm), “Hieu” (Filial Piety), “Trung” (Loyalty). Students and scholars typically seek “Minh” (Brightness), “Dang Khoa” (Successful Candidate in the Imperial Examination), and “Tri Tue” (Wisdom). For the elderly, characters like “Phuc,” “Loc,” and “Tho” are indispensable, while businessmen often look for “Loc” (Prosperity), “Tin” (Trust), and “Phat” (Development). Written on red or pink paper, symbols of good luck and well-being, the characters are crafted in black ink or gold leaf, depending on their content, to suit the person requesting them. Each character is tailored to the individual’s circumstances and work, embodying their hopes for the new year.

This tradition of requesting and giving calligraphy is a beautiful aspect of Vietnamese culture, a gift with social, philosophical, and spiritual significance. It fosters cultural exchange within the community, uniting people in their pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty. It also exemplifies the Vietnamese tradition of valuing education and the importance of literacy.

Department for Heritage Research and Collection