The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu): A Significant Daoist Architecture of the Nguyễn Dynasty

The article will be divided into two parts: Part one introduces The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion: A Significant Daoist Architecture of the Nguyễn Dynasty within the Thang Long Imperial Citadel Heritage Site – Hanoi; Part two: Distinctive Features of the Architecture and Decorative Art of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion Monument

By Đỗ Đức Tuệ, M.A.

The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu) was constructed by Emperor Minh Mạng in October 1821 within the inner sanctum of the Hanoi Citadel’s imperial residence (now part of the central area of the Thang Long Imperial Citadel – Hanoi). Built entirely of brick, its architectural design follows a symmetrical, radial structure with three compartments, three tiers, and three roofs, adorned with exceptionally refined decorative elements. On the second tier, statues of the Tam Tôn were placed to invoke blessings for the people. Over more than two centuries, the pavilion has undergone a complex process of transformation, yet its fundamental original features remain intact. During these transformations, the structure acquired alternative names, such as Hậu Lâu and Pagode de Dames (Pagoda of the Ladies), the latter emerging when French forces occupied the Hanoi Citadel in 1882. This article will examine the history of its construction, the phases of its transformation, its symbolic functions, and its chronology. Through this analysis, I argue that the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion is an original structure with deep connections to Daoism, playing a critical role for the Nguyễn dynasty within the imperial residence of Bắc Thành (Hanoi) in the 19th century.

I hereby would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Associate Professor Dr. Tống Trung Tín, President of the Vietnam Archaeological Association, for his insightful guidance and sharp observations during the reexamination of this monument. I am also deeply appreciative of Mr. Lại Quý Dương (a teacher at Bắc Đông Quan High School, Thái Bình) for his dedication to heritage conservation and his valuable contributions in providing historical evidence and suggestions, which have greatly enhanced this article on the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion.

- Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion: The Nguyễn Emperors’ Aspiration for Stability

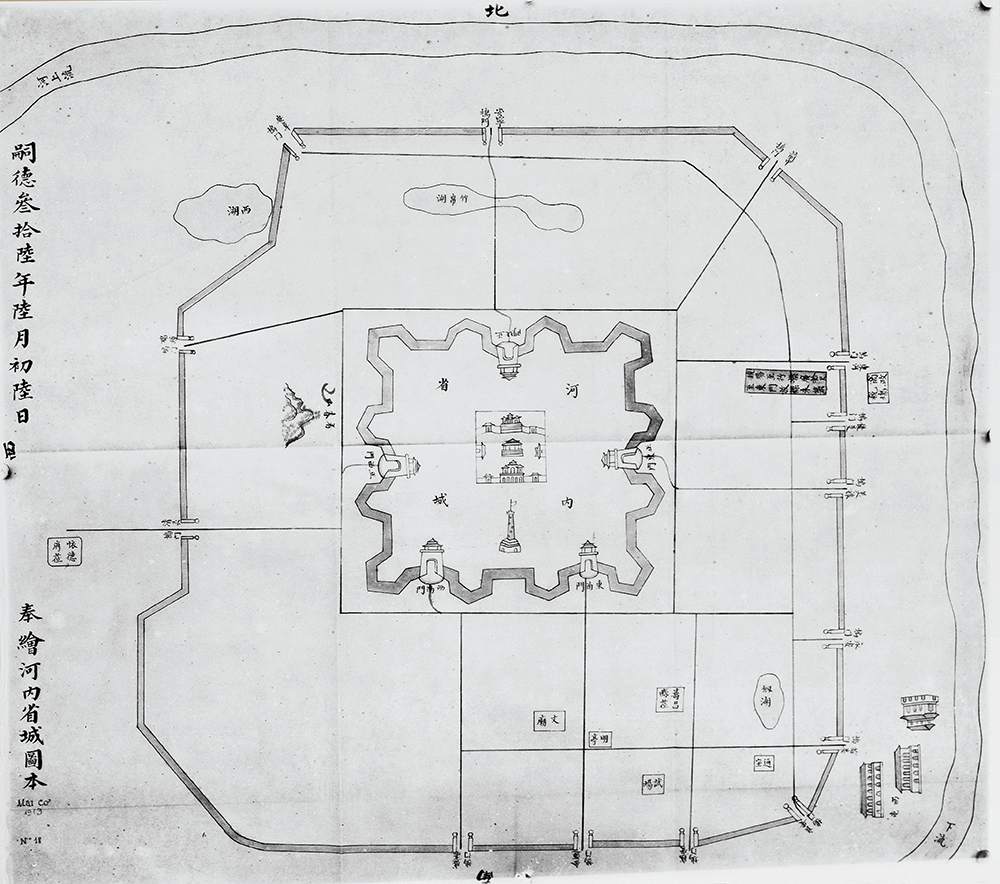

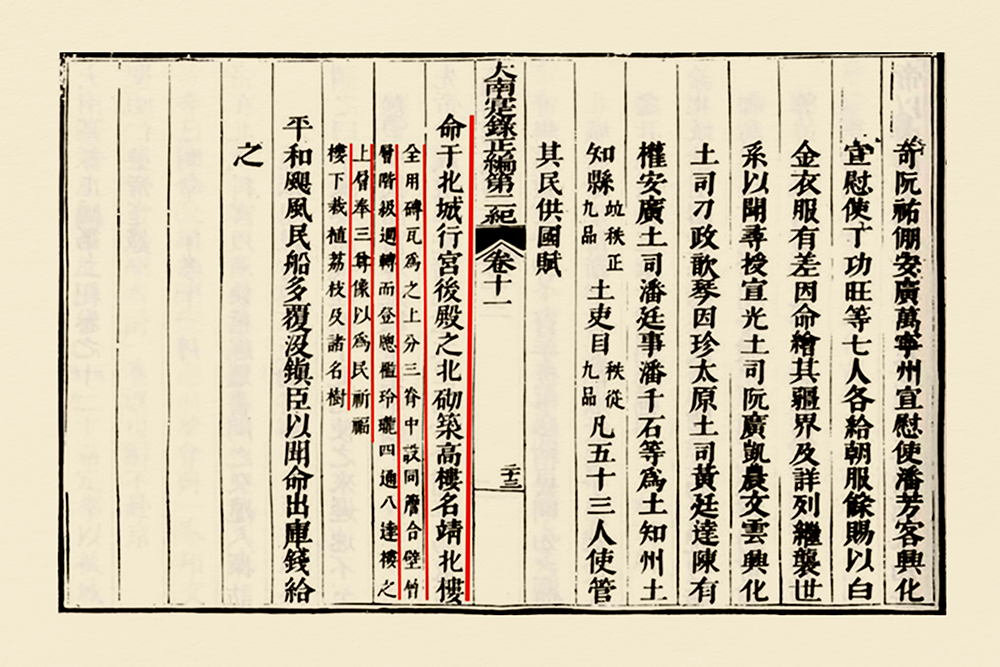

Following the establishment of the Nguyễn Dynasty, Emperor Gia Long designated Huế as the imperial capital. In 1803, he ordered the demolition of the Lê Dynasty’s Thăng Long Citadel to construct a new fortress in the Vauban style, which retained the name “Thăng Long” (升龍), symbolizing prosperity (see Image 1). Within this citadel, he built the Flag Tower and the Imperial Residence (Hành cung), which served as the administrative headquarters for the Governor of Bắc Thành—a region comprising 11 provinces. This residence became a key center of economic, political, and cultural activity and the sole venue for grand diplomatic ceremonies with the Qing Dynasty (China) during the first 46 years of the Nguyễn Dynasty (1802–1848). In 1820, Emperor Minh Mạng commissioned the reconstruction of the Bắc Thành Imperial Residence. In October 1821, while stationed in Thăng Long, the emperor ordered the construction of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion. According to the Đại Nam Thực Lục Chính Biên (Chronicles of Đại Nam), “The emperor ordered the construction of a tall pavilion to the north of the rear hall of the Bắc Thành Imperial Residence, naming it Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (靖北楼). The entire structure was built using bricks and tiles. It featured three tiers with layered roofs connected by a single wall, and each floor was accessible via a spiral staircase. The windows and balconies were delicately crafted, offering a clear view in all directions. The uppermost tier housed statues of the Tam Tôn (三尊像) to pray for blessings for the people, while the area beneath the pavilion was planted with litchi trees and other valuable flora” [1] (see Image 2). The name “Tĩnh Bắc” combines two Chinese characters: Tĩnh (靖), meaning peace or tranquility, and Bắc (北), referring to Bắc Thành. Together, the name embodies the aspiration for Bắc Thành to remain peaceful, with harmony prevailing in all directions.

Image 1: Overview of Hanoi Citadel and the Bắc Thành Imperial Residence, dated to the 36th year of Emperor Tự Đức’s reign (1883). The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion is depicted behind the Long Thiên Hall (Source: EFEO, 2010).

During the reign of Emperor Thiệu Trị, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion played a prominent role during his northern tour and the grand diplomatic ceremony with the Qing Dynasty held at the Kính Thiên Hall from January to April 1842. In February 1841, the emperor ordered Prince Hồng Hưu to organize a ritual at the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion to honor Quan Thánh Đế Quân, the deity of loyalty and righteousness, at the Hán Thọ Đình Hầu (Marquis of Longevity) Temple [2]. Around the same time, while discussing the scenic beauty of Hồ Tây (West Lake) with his court official Trương Đăng Quế, Emperor Thiệu Trị lavished praise on the architectural splendor of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, describing it as “a towering structure, reaching toward the heavens, the likes of which are rarely seen in history” [3]. Although Emperor Thiệu Trị returned to Huế in April 1842, in October of the same year, he commanded his court to select poems from his northern tour and ensure their preservation for posterity, celebrating the nation’s sublime landscape. Of the 173 poems composed during his journey, 18 were engraved on stone, while three—“Hoằng Phúc Pagoda” in Quảng Bình, “Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion,” and “Chân Vũ Shrine” in Hanoi—were inscribed on horizontal plaques to be displayed prominently at the respective sites [4]. These events underscore the enduring significance of the name “Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion,” originally bestowed by Emperor Minh Mạng. Not only did Emperor Thiệu Trị uphold this name, but he also elevated the structure, lauding it as an architectural rarity that reflected the glory of the Nguyễn Dynasty’s two-century-long legacy [5]. Based on its architecture and the rituals performed within, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion is identified as a quintessential Daoist temple. It held supreme importance as a site where the emperor prayed for blessings upon the people of Bắc Kỳ (Northern Vietnam). It symbolized the Nguyễn emperors’ aspirations for universal harmony (Thiên hạ thái bình) and the enduring prosperity of the nation (Quốc gia trường tồn).

Image 2: Document recording the construction of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion in the 2nd year of Emperor Minh Mạng’s reign (1821), from Đại Nam Thực Lục Chính Biên, Second Series, Volume 11, page 1585(167). (Source: The Oriental Institute, Keio University).

- Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion – Hậu Lâu: A History of Decline and Transformation

Hậu Lâu, another name for the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, likely emerged during a period of decline for the Hà Nội Imperial Residence (Hành cung Hà Nội). This downturn began in May of the third year of Emperor Tự Đức’s reign (1849), when the grand diplomatic ceremony with the Qing Dynasty was officially relocated to the imperial capital of Huế. This pivotal shift led to the cessation of all construction activities at the Bắc Thành Imperial Residence. Many structures were dismantled and redistributed to Sơn Tây and Nam Định provinces or transported to Huế. The once grand Hà Nội Imperial Residence, planned as a miniature version of the Đại Nội (Imperial City), was reduced to just the Long Thiên Hall and the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion. Hà Nội and its Hành cung (Imperial Residence) were thus demoted to the status of a provincial town. Photographs taken by Émile Gsell in 1873

Image 3: Section inside Hanoi Citadel from Long Thiên Hall to Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, viewed from the East Gate. Photograph by Émile Gsell, 1873 (Source: Citadelle de Hanoi, EFEO, 2010)

[6] from the East Gate of Hà Nội Citadel show the central area of Long Thiên Hall surrounded by an expansive empty space extending to the base of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (see Image 3). Without the support of the inner palace of the Hành cung, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion gradually lost its prominence, and the name “Hậu Lâu” emerged. This designation primarily reflected its positional significance as the “rear pavilion” behind the main hall of the Hành cung. The exact origin of the name “Hậu Lâu” remains uncertain. According to Professor Hoàng Xuân Hãn’s writings in Các Văn cổ về Hà Thành thất thủ và Hoàng Diệu (Ancient Texts on the Fall of Hà Nội and Hoàng Diệu), it was on April 25, 1882, during the French assault on Hà Nội Citadel, that the gunpowder depot at Hậu Lâu exploded. It is said that Hoàng Diệu, the governor of Hà Nội, had hidden gunpowder in the Hậu Lâu warehouse [7]. Following the French victory, they initiated forced interventions to erase traditional elements of the ancient citadel, replacing many historic structures, including Long Thiên Hall, with colonial buildings that symbolized the power of the French regime. The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion was not exempt from these interventions, though the extent of the alterations—whether it was fully demolished or merely transformed—remains unclear. Photographs of Hậu Lâu from approximately 1885–1887 reveal that the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion had been repurposed as a French military defense station. The lower levels had their doors on the first and second floors boarded up with wooden planks, and a signal transmission mast was installed atop the central roof (see Image 4). The windows were later sealed with mortar, leaving only small loopholes for observation and defense. One photograph carries the caption HaNoi Pagode de Hao Loa (Pagode des Dames) or “Pagoda of the Ladies,” referring to the Hậu Lâu (see Image 5). It is likely during this period that the French removed the original Daoist altars from the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion. Unfortunately, there are few surviving photographs from this time that document the pavilion’s internal changes. Between 1894 and 1900, Hà Nội and its central areas experienced the most severe destruction, alongside intensive new construction under French administration. During this time, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu) underwent significant alterations in both its appearance and function, transforming it into a permanent French military garrison. A 1905 map of the military district indicates the area from Long Thiên Hall to Hậu Lâu as E – Direction d’Artillerie (Artillery Headquarters). It also shows three barracks structures and two smaller buildings flanking Hậu Lâu [8].

Image 4: Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu), photographed in 1885, with doors and windows temporarily boarded up with wooden planks. (Source internet: manhhai, flickr, 2019).

Image 5: Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu), photographed in 1885–1886, with windows sealed and loopholes added (Source: manhhai, flickr, 2020)

After the liberation of Hanoi in October 1954, the Hanoi Citadel became the headquarters of the General Command [9], The architecture of Hậu Lâu was preserved intact during the handover from the French military. Between 1998 and 1999, as part of a series of historical and cultural research activities organized by Hanoi to commemorate the 990th anniversary of Thăng Long – Hanoi and to prepare for the Millennium Celebration of Thăng Long – Hanoi, several field studies focusing on the history, architecture, and archaeology of the central area of the Hanoi Citadel were initiated. However, these studies were conducted on a relatively modest scale. Archaeological excavations at the Hậu Lâu site uncovered a dock, a well, and a significant collection of royal ceramics from the Early Lê Dynasty. These findings provide compelling evidence that this area once served as a residential space for the royal family during the Lê period [10].

Image 6: The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu) prior to renovation, photographed in 1999–2000. (Source: World Heritage Nomination Dossier, 2010)

Image 7: Detail of the rear annex behind Hậu Lâu. (Source: Trần Thanh Nhân, Hà Nội – Past and Present, 2009)

As for the architecture of Hậu Lâu, its state during this period featured a three-story structure with a two-story rear annex attached to its back. The building was painted in a reddish-purple hue, which had faded over time. The first floor had a central entrance, leading to a large interior room supported by four pillars, two of which were round steel columns embossed with the inscription “Baudet-Donon & Cie à Paris.” Behind the steel columns was the main door that provided access to the annex, which contained a small corridor leading to two side rooms. In these rooms, a narrow and steep staircase led to the second floor. The walls were 67 cm thick, and the plaster remained relatively intact. The doors and windows were equipped with green-painted wooden panel shutters with jalousie slats. The roof of the pavilion and the annex featured curved designs characteristic of traditional Vietnamese architecture. However, a chimney—indicative of a French-style fireplace—was present on the roof of the western wing (see Images 6–7). Surveyors noted that certain technical elements and architectural features were reminiscent of other French colonial structures in the area. In 2002, the Hanoi Department of Culture and Sports carried out renovations, during which the rear annex was dismantled, the central door and side windows were sealed, and the wooden shutters were removed, restoring the structure to its current appearance. The name “Hậu Lâu,” as an alternative to Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, appeared in documents and photographs from the late 19th century. Hậu Lâu reflects not only the decline of the Hà Nội Imperial Residence but also the architectural transformations and interventions made by the French military. Some of these elements remain visible in the monument today.

- The Function and Historical Significance of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion

Image 8: Tam Thanh statues at Hưng Thánh Temple (Chùa Mui), Thường Tín, Hanoi (Source: Internet, bachviet18)

According to the Đại Nam Thực Lục compiled by the National History Bureau of the Nguyễn Dynasty, the second floor of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion was dedicated to enshrining statues of the Tam Tôn (三尊像) for the emperor to pray for blessings upon the people of Bắc Kỳ (Northern Vietnam). To begin, it is necessary to clarify the term Tam Tôn. This term refers to supreme deities in either Daoism or Buddhism. In the absence of the original statues, the identification of these deities relies entirely on the architectural features [11] and symbolic decorations preserved in the monument. The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, with its towering structure reaching skyward, was designed to honor celestial deities. Moreover, its decorative features reflect distinctive characteristics of both Daoist and Confucian traditions. Consequently, it can be hypothesized that the Tam Tôn venerated on the second floor of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion represented the three supreme Daoist deities: Ngọc Thanh Nguyên Thủy Thiên Tôn (玉淸元始天尊), Thượng Thanh Linh Bảo Thiên Tôn (上淸靈寶天尊主), and Thái Thanh Đạo Đức Thiên Tôn (太淸道德天尊) (see Image 8). These deities were widely worshiped during the Lý, Trần, Lê, and Mạc Dynasties to pray for blessings and longevity for the nation and its people. However, during Emperor Thiệu Trị’s reign, official records provide a more detailed account. In February of the second year of his reign (1842), while discussing the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion with his court official Trương Đăng Quế at the Hà Nội Imperial Residence, the emperor not only praised the architectural beauty of the pavilion but also provided the following explanation: “This pavilion was constructed in the second year of Minh Mạng’s reign (1821) using bricks and tiles. It is divided into separate sections: the central section is dedicated to Huyền Thiên Chân Vũ Đại Đế (玄天真武大帝), the left section to Buddha Già Lam, and the right section to Ngô Đạo Tử. The pavilion was established with the purpose of offering blessings to Northern Vietnam, hence its name, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion.” [12].

Huyền Thiên Chân Vũ, also referred to as Thần Huyền Vũ or Huyền Thiên Thượng Đế, holds a prominent place in Daoist cosmology. According to the Thái Thượng thuyết Huyền Thiên Đại Thánh Chân Vũ Bản truyện Thần chú diệu kinh (The Supreme Exposition on the Mysterious Heavenly Great Sage Chân Vũ’s Sacred Incantation and Biography), Chân Vũ Đại Đế was the 82nd incarnation of Thái Thượng Lão Quân (the Supreme Elder Lord). Born in the celestial realm of Đại La Cảnh Thượng Vô Dục Thiên Cung, Chân Vũ left his home upon reaching maturity, bidding farewell to his parents to ascend Mount Vũ Đương, where he pursued Daoist cultivation. After 42 years of devoted practice, he attained spiritual perfection and ascended to the heavens in broad daylight. The Jade Emperor then decreed that Chân Vũ would be titled Thái Huyền and appointed as the guardian deity of the North. Known as Huyền Vũ, the deity is associated with the seven northern constellations of the Nhị thập bát tú (Twenty-Eight Lunar Mansions). In Vietnamese tradition, Huyền Vũ is revered as Huyền Thiên Trấn Vũ, a major deity in Daoism who governs the North and rules over aquatic creatures, earning him the titles of Water God (Thủy Thần) or Sea God (Hải Thần) [13]. In the imperial capital of Thăng Long (modern-day Hanoi), the deity is venerated at Trấn Vũ Temple, situated in the northern part of the city. As one of the Tứ Trấn (Four Sacred Guardians) protecting the Thăng Long Citadel, Trấn Vũ enjoys deep reverence among the people. Other notable temples dedicated to him in Hanoi include: Huyền Thiên Cổ Quán (Huyền Thiên Pagoda) on Hàng Khoai Street; Huyền Thiên Đại Quán (Đền Sái) in Thụy Lôi, Đông Anh; Đền Trấn Vũ in Thạch Bàn, Long Biên; Đền Đồng Thiên (Kim Cổ Pagoda) on Đường Thành Street.

The deity referred to as Phật Già Lam, worshiped in the left wing of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, is likely Quan Vũ, the guardian deity of Buddhist monasteries (Già Lam). According to the Phật Tổ Thống Ký (Records of the Buddha’s Lineage), General Quan Vũ (also known as Guan Gong) of the Three Kingdoms period became a deity after his death and later adopted the Five Precepts of Buddhism, transforming into a Dharma Protector within the Buddhist tradition [14]. A significant detail supporting the identification of Phật Già Lam as Quan Vũ is the event in February 1842 when Emperor Thiệu Trị ordered Prince Hồng Hưu to conduct a ritual honoring Hán Thọ Đình Hầu Quan Thánh Đế Quân (the Marquis of Hán Thọ, the title of Quan Vũ) [15]. This title, Hán Thọ Đình Hầu, symbolizes loyalty, filial piety, and righteousness, qualities for which Quan Vũ is renowned. In Chinese religious history, Quan Vũ is an extraordinary figure, evolving from a mortal into a saintly being and achieving immense status as the “Foremost Divine Being” (Đệ nhất Thần minh), venerated across the Three Teachings (Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism). Confucianism honors Quan Vũ for his exemplary loyalty and righteousness, which align with the Confucian ethical principles of filial piety and moral integrity. Buddhism venerates Quan Vũ for his miraculous appearances and contributions to the establishment of temples, fostering a unique spiritual connection. Daoism regards Quan Vũ as a deity who suppresses demons and restores peace, invoking his power to ward off evil. The worship of Quan Vũ extends far beyond China, spreading through Chinese diaspora communities and gaining significant influence in countries worldwide, including Vietnam [16].

Ngô Đạo Tử, a renowned Chinese painter of the Tang Dynasty (circa 685–758), rose from humble beginnings as an ordinary artisan to achieve legendary status as a master of painting, earning him the title “Họa Thánh” (Saint of Painting). His extraordinary skill in artistic expression, particularly in the realm of religious art, left a profound legacy in both Buddhist and Daoist traditions. Ngô Đạo Tử is credited with creating hundreds of murals for Buddhist and Daoist monasteries, solidifying his reputation as a pioneering figure in religious art [17]. The enshrinement of Ngô Đạo Tử in the right wing of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion raises intriguing questions regarding his veneration within this architectural context.

It can thus be affirmed that the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion is a Daoist structure where the Nguyễn royal family conducted rituals to pray for blessings and peace in Bắc Kỳ, symbolizing their aspiration for “peace under heaven” and the nation’s prosperity [18]. However, a point of uncertainty arises: historical records from the second year of Emperor Minh Mạng’s reign (1821) state that the upper level of the pavilion enshrined the Tam Tôn. Based on the architectural features and the remaining artifacts, we identify the Tam Tôn as the three supreme Daoist deities: Ngọc Thanh Nguyên Thủy Thiên Tôn, Thượng Thanh Linh Bảo Thiên Tôn, and Thái Thanh Đạo Đức Thiên Tôn. The spatial arrangement and Daoist symbolism in the central chamber of the second floor align perfectly with a sacred space designed to honor these three deities, who are traditionally worshiped together on a shared altar. Nevertheless, a later account from February 1842 provides a different description, stating that the second floor was divided into three sections: the central section was dedicated to Huyền Thiên Chân Vũ, the left wing to Phật Già Lam (Quan Công), and the right wing to Ngô Đạo Tử. This discrepancy raises a significant question: were the Tam Tôn venerated during Minh Mạng’s reign the same as the three figures worshiped during Thiệu Trị’s reign? This inconsistency suggests the possibility that the deities enshrined at the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion may have changed over time, warranting further investigation into the evolution of its sacred functions and symbolic meanings.

- Architectural Transformations of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion and the Chronology of the Monument

The architectural transformations of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion primarily occurred during the French colonial period, involving highly complex and unpredictable interventions at various times. These changes, coupled with challenges in directly accessing the monument (due to its management by the military), have made studying the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu) particularly difficult. For instance, when studying the Hanoi Citadel, Hanoi scholar Nguyễn Văn Uẩn observed, “Behind the Kính Thiên Hall, the Hậu Lâu Temple no longer exists; that area has become a row of single-story barracks” [19]. Similarly, French scholar Olivier Tessier noted, “By 1873, the Hậu Lâu (built in 1821) was already in a state of ruin” [20]. These scholarly opinions, alongside others that support similar views, underscore the complexity of clarifying the historical and architectural significance of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu). Despite these challenges, in 2024, the Thang Long – Hanoi Heritage Conservation Center conducted comprehensive research on the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, focusing on various aspects of its history, artistic features, and architectural characteristics. This study has been particularly significant in delineating the stages of transformation and providing a solid foundation for evaluating the monument’s chronology.

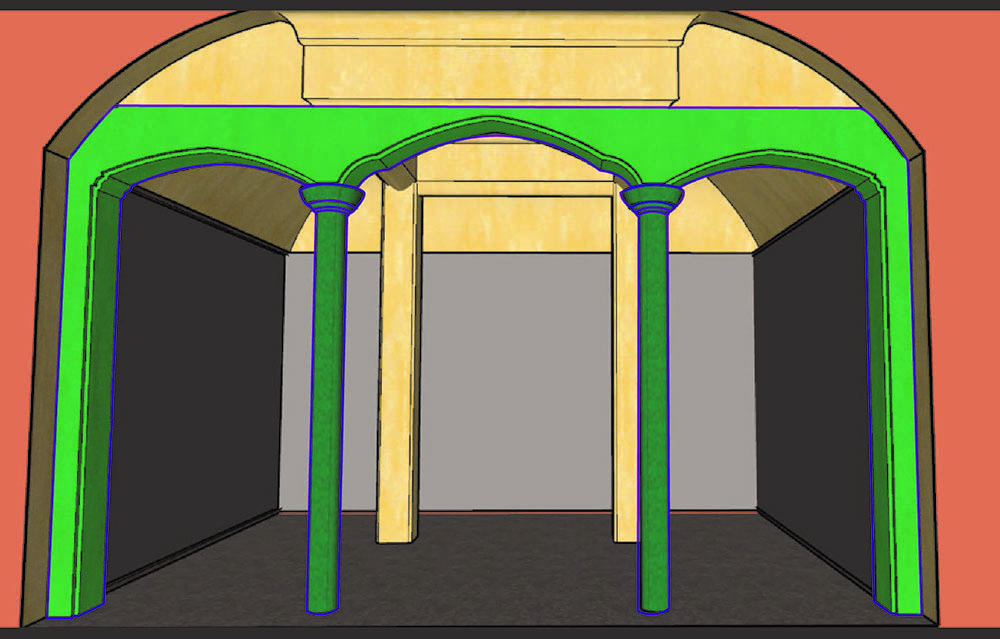

Image 9: Simulation of architectural modifications inside the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion by the French military. The sections highlighted in blue indicate areas renovated by the French. (Source: Thang Long – Hanoi Heritage Conservation Center).

Image 10: Detail of the round iron column embossed with the inscription “Baudet-Donon & Cie à Paris”. (Source: Thang Long – Hanoi Heritage Conservation Center).

To determine the chronology of the Hậu Lâu monument, it is necessary to analyze the later components layer by layer across different time periods. First, we arranged photographs taken by the French in chronological order to track the transformations of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion. At the site itself, we evaluated areas renovated in 2002 and during the period of French intervention. A significant breakthrough was made by examining two iron columns bearing the embossed inscription “Baudet-Donon & Cie à Paris” and their relationship to the brick architrave located above the doorway. The iron columns were likely replacements introduced to support the upper floors while simultaneously bearing the load of the decorative brick architrave. This architrave, crafted in a traditional Vietnamese style, functioned as an ornamental feature positioned in front of the rear annex entrance (see Images 9–10). Therefore, the iron columns serve as a critical element in identifying the major renovation conducted by the French military. According to Jean Lambert-Dansette’s Enterprises and Entrepreneurs in France, published in 2009 [21], the Baudet-Donon & Cie company was based in Paris and established in 1878. In 1921, it merged with the Roussel company to become Baudet-Donon-Roussel. Specializing in steel construction, railway manufacturing, and mineral extraction, Baudet-Donon & Cie was one of six companies that bid on the construction of the Long Biên Bridge in Hanoi, though it did not win the contract [22]. Based on this information, the French military renovation of Hậu Lâu can be dated no later than 1921, the final year the Baudet-Donon company’s branding appeared on its steel products. This timeline is further supported by an aerial photograph of the Hanoi Citadel area, taken between 1926 and 1930, which confirms that the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion had undergone modifications by that time (see Image 11).

Image 11: Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (circled) in an aerial photograph of the Hanoi Citadel, taken between 1926–1930. The central door was added, and the rear annex was constructed. (Source: Internet, manhhai, Flickr, 2022).

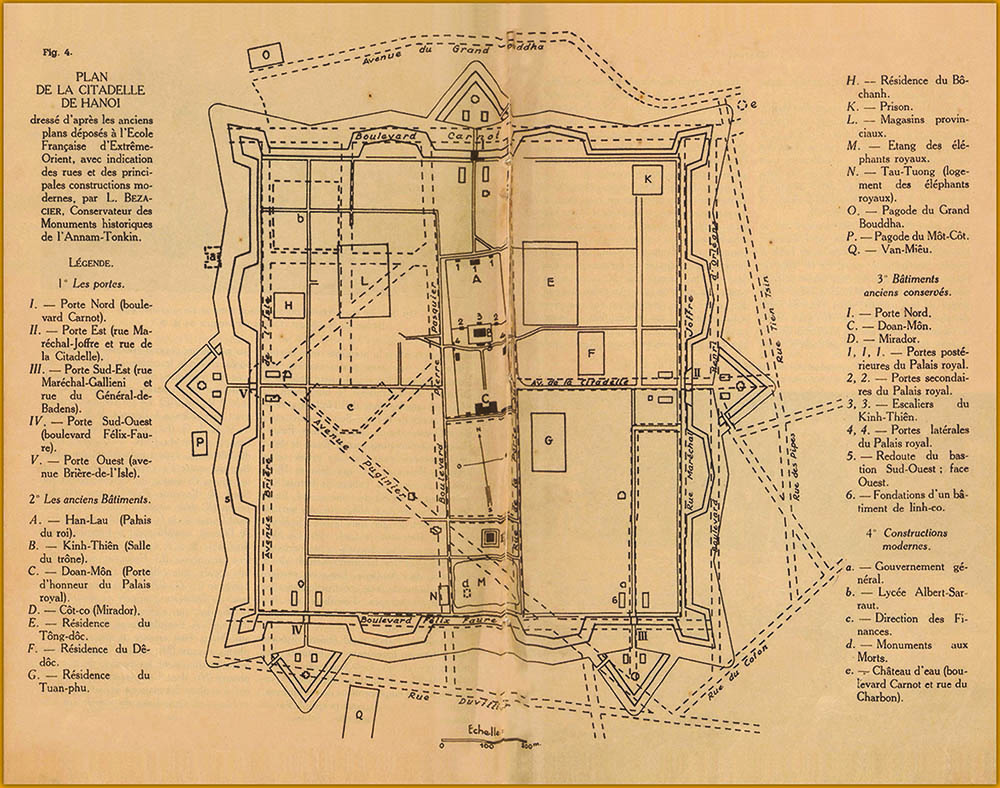

Image 12: A map of Hanoi Citadel created by L. BEZACIER in 1942. (Source: National Archives Center I).

Another significant piece of evidence is a map of Hanoi Citadel created by L. BEZACIER in 1942. This map includes street layouts, major new structures, and historical buildings (Hậu Lâu – A, Kính Thiên – B, Đoan Môn – C, and Cột Cờ – D). As a renowned researcher of Vietnamese architecture and cultural history, Bezacier had the opportunity to directly observe the monument during this period. He labeled Hậu Lâu as “Palais du roi,” meaning “Palace of the King,” which further confirms that despite renovations, Hậu Lâu retained much of its original architectural form (see Image 12).

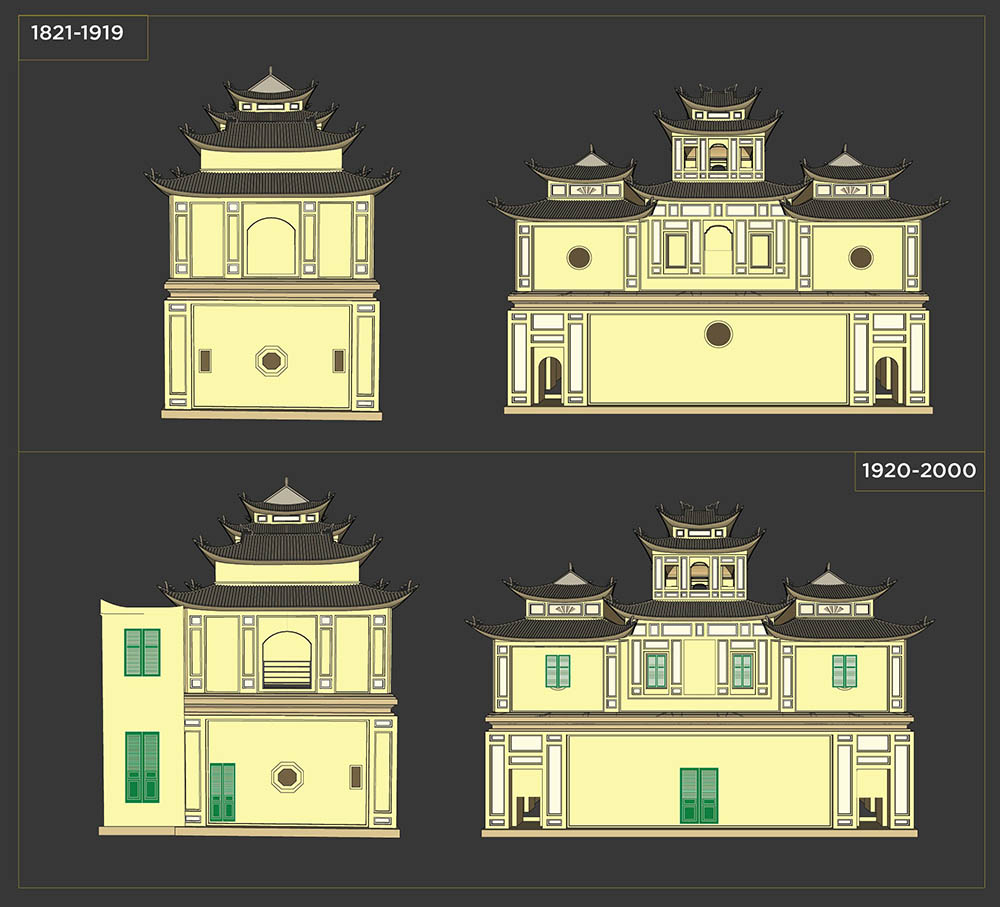

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the transformation of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion only began with French colonial intervention in the Hanoi Citadel area. This process can be divided into two phases:

Phase 1 (1885–1887): During this period, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion was converted into a defensive station. French soldiers removed decorative elements, such as the sun emblem or the gourd at the peak of the third-floor roof, to install an antenna mast. Doors and windows were sealed, leaving only small loopholes for defense. However, the interventions during this phase were relatively minimal.

Phase 2 (1910–1921): This period witnessed the most extensive architectural interventions. The French military constructed a large two-story annex at the rear of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion, directly connected to the central chamber. This addition triggered a series of systematic changes, including: The replacement of two square columns with round iron columns embossed with the inscription “Baudet-Donon & Cie à Paris”. The construction of a decorative architrave above the two iron columns at the entrance to the annex. The addition of a central doorway as the main entrance to the structure. The creation of a secondary entrance on the western side. Modifications to the second-floor windows, which were outfitted with wooden shutters. The installation of a fireplace and a chimney protruding from the roof of the western wing.

Image 13: Simulation of the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (Hậu Lâu)’s exterior structural transformations over time. (Source: Thang Long – Hanoi Heritage Conservation Center).

Conclusion

The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion (also known as Hậu Lâu) is a significant monument of the Nguyễn Dynasty preserved within the Thang Long Imperial Citadel heritage site. It can be affirmed that the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion is a Daoist structure dedicated to the worship of the Tam Tôn, where Nguyễn emperors conducted rituals to pray for blessings and peace for the people of Bắc Kỳ, reflecting their aspiration for harmony and stability in Bắc Thành, as encapsulated in the name Tĩnh Bắc Lầu (靖北楼). Over more than two centuries, the pavilion has also been referred to by other names, such as Hậu Lâu and the Pagode des Dames (Pagoda of the Ladies). Moreover, the structure underwent renovations and expansions by the French military during their occupation of the Hanoi Citadel from 1883 to 1954. Based on its current state and reliable historical sources, the Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion is confirmed as an original architectural relic with an absolute date of construction (October 1821). It holds exceptional value in terms of artistic design, construction techniques, and building technology from the early Nguyễn Dynasty. The Tĩnh Bắc Pavilion stands as a vivid testament to the continuity of a center of power, as well as the technological and cultural exchanges between East and West. These core values not only authentically reflect the history of Thăng Long – Hanoi but also enhance and reinforce the outstanding universal value of the Thang Long Imperial Citadel as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- [1]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume II, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 16

- [2]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume VI, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 315

- [3]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume VI, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 318.

- [4]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume VI, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 417.

- [5]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume VI, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 417.

- [6]Exhibition Thành Hà Nội – Citadelle de Hanoi (EFEO, 2010.

- [7]Hoàng Xuân Hãn, Các Văn cổ về Hà Thành thất thủ và Hoàng Diệu, supplementary section, p. 21.

- [8]Map titled Place de Hanoi Citadelle Plan d’ensem (Scale 1/500), annotated in Tonkin Atlas de Bâtiments Militaires (EFEO, 2010).

- [9]This was also the General Headquarters, where the Politburo, Central Military Commission, General Command, and General Staff worked, led, and commanded during the period of peace-building and the resistance war against the United States. From 2004, the Ministry of National Defense gradually transferred the Hanoi Citadel relic site to the Hanoi People’s Committee for research and preparation of the nomination dossier for the Thang Long Imperial Citadel to be recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In September 2010, the site was officially designated a World Heritage Site, and research, conservation, and promotion efforts intensified. The integration of management was one of the commitments made by the Prime Minister to UNESCO, finalized in November 2024 by the Ministry of National Defense and the Hanoi People’s Committee, marking a significant achievement praised by UNESCO.

- [10]Tống Trung Tín and Hà Văn Cẩn, 1998, Thám sát khai quật địa điểm Hậu Lâu (Hà Nội), Phases 1 and 2, Institute of Archaeology Archive.

- [11]Daoism is a polytheistic religion that venerates celestial stars, which are also considered divine beings. Thus, typical Daoist architecture includes “quán” (temples), located on mountain peaks, or multi-story structures rising skyward on flat plains, referred to as “lâu” (pavilions). These serve as places for Daoist practices and religious ceremonies. Depending on the architectural scale, Daoist temples may be called điện, đường, phủ, miếu, am, lâu, xá, trai, or các. In addition to architectural features, the artistic decorations of these temples have highly symbolic elements unique to Daoism (https://vi.wikipedia.org).

- [12]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume VI, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 318.

- [13]https://www.luongthienxich.com/2023/09/than-tich-ve-uc-huyen-thien-chan-vu-ai-e.html.

- [14]https://phatgiao.org.vn/gia-lam-co-them-mot-vi-ho-phap-d77823.html, posted on 25/09/2023, 17:12 pm.

- [15]Đại Nam thực lục chính biên, Volume VI, translated by the Institute of History, Giáo Dục Publishing House, 2007, p. 315

- [16]Nguyễn Thái Hòa (2019), Tín ngưỡng thờ Quan Công của người Hoa ở Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (trường hợp ở Nghĩa An hội quán), published on https://thanhdiavietnamhoc.com ngày 8/11/2019.

- [17]https://www.epochtimesviet.com/hoa-thanh-ngo-dao-tu_410265.html, posted on 20/9/2023.

- [18]According to Nguyễn Quốc Hùng: “Huyền Thiên Trấn Vũ, the deity who guards the North, represents a highly strategic direction for Vietnam. The nation’s safety during the medieval period seemed to hinge on the North. Therefore, the existence of Trấn Vũ Temple is tied to the survival of Daoist thought and its connection to the nation’s stability.” (Nguyễn Quốc Hùng, 2010, Khái lược về Đạo giáo và Đạo quán ở Việt Nam, Journal of Cultural Heritage, No. 2(31)-2010, pp. 64–69).

- [19]Nguyễn Văn Uẩn, 1994, Hà Nội nửa đầu thế kỷ XX, Volume 1, Hanoi Publishing House, p. 257

- [20]Andrew Hardy and Nguyễn Tiến Đông (eds.), 2018, Phát lộ di tích Hoàng thành Thăng Long – Thoáng nhìn đầu tiên về di sản khảo cổ học, Thế giới Publishing House, p. 303

- [21]Jean Lambert-Dansette, Histoire de l’entreprise et des chefs d’entreprise en France, L’Harmattan, 2009, tome 5, p. 179.

- [22]Six major French companies bid on the Long Biên Bridge construction project: Levallois-Perret, Daydé et Pillé, Schneider et Cie (Creusot), Fives-Lille, Joret, and Baudet Donon Paris. Ultimately, Daydé et Pillé won the contract.